By the early 1970s, Don Hoefler, a writer for Electronic News, was spending after-hours at his “field office” — a faux-Western tavern known as Walker’s Wagon Wheel, in Mountain View, Calif. In a town with few nightspots, this was the bar of choice for engineers from the growing number of electronic and semiconductor chip firms clustered nearby.

Hoefler had a knack for slogans, having worked as a corporate publicist. In a piece published in 1971, he christened the region — better known for its prune orchards, bland buildings and cookie-cutter subdivisions — “Silicon Valley.” The name stuck, Hoefler became a legend and the region became a metonym for the entire tech sector. Today its five largest companies have a market valuation greater than the economy of the United Kingdom.

How an otherwise unexceptional swath of suburbia came to rule the world is the central question animating “The Code,” Margaret O’Mara’s accessible yet sophisticated chronicle of Silicon Valley. An academic historian blessed with a journalist’s prose, O’Mara focuses less on the actual technology than on the people and policies that ensured its success.

She digs deep into the region’s past, highlighting the critical role of Stanford University. In the immediate postwar era, Fred Terman, an electrical engineer who became Stanford’s provost, remade the school in his own image. He elevated science and engineering disciplines, enabling the university to capture federal defense dollars that helped to fuel the Cold War.

Terman also built one of the first academic research parks, leveraging Stanford’s extensive real-estate holdings in the Santa Clara Valley. Among the businesses he persuaded to move to the area were Hewlett-Packard and a company owned by William Shockley, the co-inventor of the transistor.

Shockley turned out to be a boss from hell, and, in a legendary rupture, a handful of his most talented employees — the “Traitorous Eight” — parted ways from him and founded Fairchild Semiconductor. Fairchild became the Valley’s ur-corporation: Its founders subsequently launched many more storied firms, from the chip maker Intel to the venture capital firm Kleiner Perkins.

O’Mara argues persuasively that Fairchild “established a blueprint that thousands followed in the decades to come: Find outside investors willing to put in capital, give employees stock ownership, disrupt existing markets and create new ones.” But she makes clear that this formula wasn’t just a matter of free markets working their magic; it took a whole lot of Defense Department dollars to transform the region. Conveniently, the Soviets launched Sputnik three days after Fairchild was incorporated, inaugurating a torrent of money into the tech sector that only increased with the space race.

Something similar happened again in the 1980s, when Ronald Reagan’s Strategic Defense Initiative and Darpa’s Strategic Computing Initiative — aimed at threats posed by the Soviet Union and Japan, respectively — funneled even more resources into the region’s companies. Defense money, O’Mara observes, “remained the big-government engine hidden under the hood of the Valley’s shiny new entrepreneurial sports car, flying largely under the radar screen of the saturation media coverage of hackers and capitalists.”

But it was how these defense dollars got distributed — via Stanford and a growing number of subcontractors in the region — that mattered as much, if not more. O’Mara argues that the decentralized, privatized system of doling out public contracts fostered entrepreneurship. So, too, did Congress, which passed the Small Business Investment Act in 1958, offering generous tax breaks to the kinds of start-ups proliferating in the shadow of Stanford.

These same factors prevailed at other aspiring tech hubs, notably Route 128 outside Boston, which housed several iconic firms, including Wang and Polaroid. Yet California eventually bested Route 128, and not just because the state had a clear edge when it came to winter weather.

The sources of its success, O’Mara contends, had to do with a host of regulations and legal decisions that governed how firms in the Valley did business. Foremost among these was California’s longstanding prohibition on noncompete clauses. This made it easy for employees to job-hop and share news of the latest innovations without fear of reprisal or recrimination. The turnover was staggering at Valley start-ups compared with established corporations such as I.B.M. on the other side of the country. But the creativity unleashed in the process left other regions far behind.

No less important was the passage of the Immigration and Naturalization Act of 1965, which unexpectedly led to an influx of newcomers, many of them skilled in the technical fields that are Silicon Valley’s bread and butter. Between 1995 and 2005, more than half the founders of companies in the Valley were born outside the United States.

But this was a later development. At first, Silicon Valley was the province of white guys in white shirts and crew cuts working for defense contractors and chip makers. They created what O’Mara memorably describes as a “profanity-laced, chain-smoking, hard-drinking hybrid of locker room, Marine barracks and scientific lab.” These men happily voted Republican, and had little interest in California’s counterculture, much less its increasingly visible feminist movement. As O’Mara notes, Silicon Valley’s gender imbalance dates back to a time when “girls and electronics didn’t mix.”

This is one of O’Mara’s strongest narrative threads: the casual misogyny that has defined Silicon Valley from past to present. She manages to bring the few women who did succeed to the forefront, most notably the programmer and entrepreneur Ann Hardy, who battled systemic sexism even as she wrote the code for many of the first computer time-sharing and networking applications built by the company known as Tymshare.

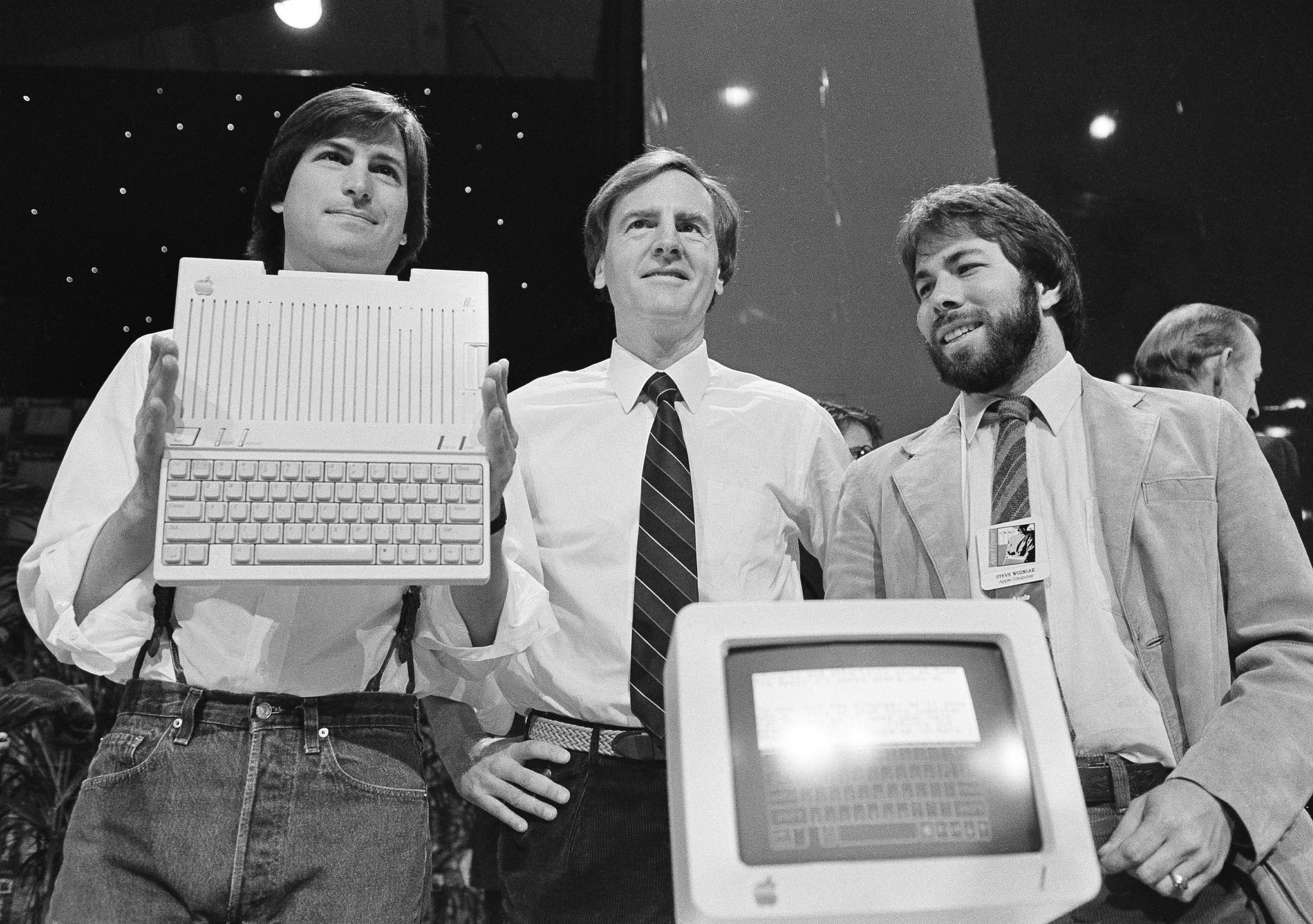

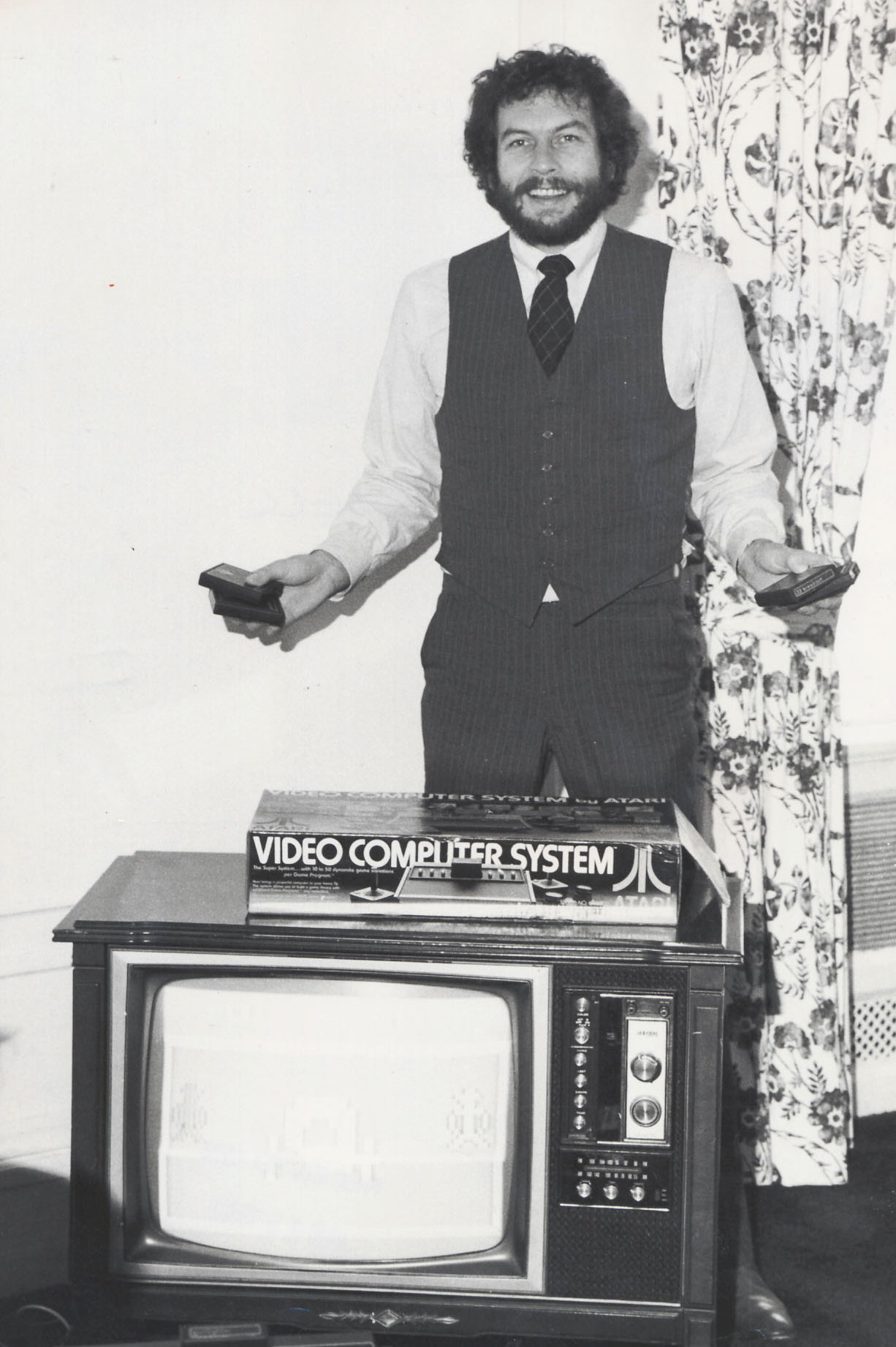

Men otherwise rule O’Mara’s book, even if, as the 1970s arrived, they increasingly came from the ranks of the phone phreaks and “longhairs.” They included Nolan Bushnell, the charismatic founder of Atari, whose band of merry nerd-bros smoked weed and made game controls shaped like breasts; the “Steves” — Wozniak and Jobs — whom one early capitalist, appalled by their lack of hygiene, described as “renegades from the human race”; and Jim Warren, the math professor and impresario who founded the West Coast Computer Faire in 1977 and published the influential, if offbeat, publication known as “Dr. Dobb’s Journal of Computer Calisthenics and Orthodontia.”

O’Mara toggles deftly between character studies and the larger regulatory and political milieu. She traces how the famously apolitical titans of tech became increasingly savvy to the ways of Sacramento and Washington. In the late 1970s, they secured cuts to the capital gains tax and changes to arcane regulations governing how easily pension funds could place money with venture capitalists. The result was a flood of new investment that revived Silicon Valley’s fortunes.

In fact, the closest Silicon Valley came to annihilation wasn’t at the hands of politicians and regulators, but rather at those of Bill Gates. O’Mara relates the epic battle between Microsoft and everyone else with admirable economy, incorporating the rise of I.B.M. clones, Netscape’s ignominious end and other low points in the Valley’s history. In a nice twist, it was Sergey Brin and Larry Page, working in the newly endowed William H. Gates Computer Science Building at Stanford, who did more than anyone else to “shove Microsoft’s Sun King off his software throne.” Their iconic firm, Google, destroyed Microsoft’s Internet Explorer and began challenging Microsoft’s core suite of office products.

By this time, “Silicon Valley” had become shorthand for an entire industry that was concentrated in Santa Clara County but had outposts in cities like Seattle, where Amazon had set up shop. The “continuing irony,” O’Mara writes, lay in the fact that “some of those most enriched by the new-style military-industrial complex were also some of the tech industry’s most outspoken critics of big government.”

The poster boy of this contradiction is the libertarian and PayPal founder Peter Thiel, who has since bankrolled another Silicon Valley data-mining firm, Palantir, named after the “seeing stones” in “The Lord of the Rings.” Palantir’s top clients? The C.I.A. and firms working for the national security state.

Can Silicon Valley — a place and state of mind — maintain its supremacy in the coming years? China is pumping staggering amounts of money into its own tech sector, while European regulators are moving aggressively to curb the power of the biggest tech companies. Here at home, the Department of Justice has signaled that it may initiate antitrust proceedings against them, while Republicans seem determined to restrict immigration to the United States, effectively cutting off the lifeblood of talent that has sustained the tech sector in recent years. If Silicon Valley wants to preserve its dominant status, it’s time to remember the words of Andy Grove, the iconoclastic C.E.O. of Intel: “Only the paranoid survive.”

Stephen Mihm is a professor at the University of Georgia. He is working on a history of standards and standardization in American life.

THE CODE

Silicon Valley and the Remaking of America

By Margaret O’Mara

496 pp. Penguin Press. $30.

How the Department of Defense Bankrolled Silicon Valley - by Stephen Mihm - New York Times - July 9th, 2019